Theatre to Therapy: Debra Hauer on a Mid-life Career Change

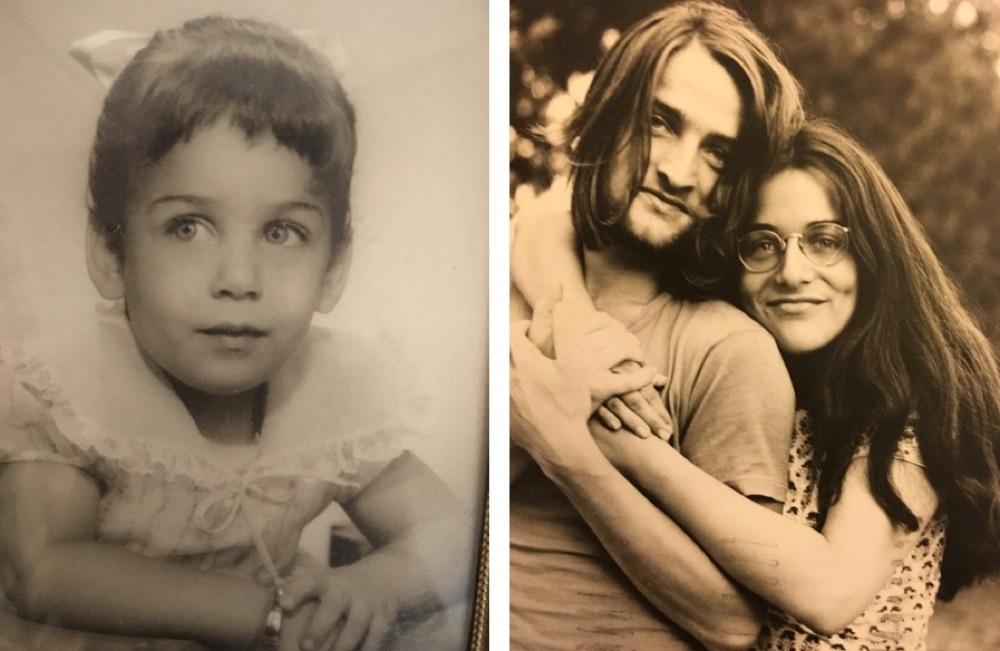

A few years ago, not long before her sixtieth birthday, Debra Hauer approached the seventh decade of her life with a burgeoning second career as an existential psychotherapist. This followed a time in her early fifties when, having had a successful previous career in theatre and television as an arts producer, she had reached a moment of reflection about her aspirations for the remainder of her working life. There had been a number of unexpected life developments in recent years (most notably, being divorced after a twenty-four year marriage) and Debra felt open to change. She was aware of several women that she knew who had decided to train as psychotherapists. “I’d seen them do it and I noticed that I felt fascinated, and very envious”, she says. “So at a certain point, I thought ‘why do I have to be envious – why can’t I just do it?'” And she did. At the age of fifty-three, she began her foundation course in psychotherapy. “And I knew as soon as I embarked that I was deadly serious and I never looked back.”

In our chat with Debra, she talks to us about the rejuvenating exhilaration she has experienced and what she has learned about herself by changing careers in her mid-life.

N.B.: Interested in meeting Debra, hearing her thoughts about her life in psychotherapy and gaining some insight into what happens in the consulting room? Book here for our next F² Fabsters Event — Psychotherapy Post-Fifty with Debra Hauer — on Monday, 12 March 2018.

Fabulous Fabsters: If you were to describe the phases of your career, what would they be?

Debra Hauer: The first phase of my career lasted about twenty years. I moved to London in 1978 straight after graduating from Swarthmore College in the US with a degree in English. I came to London to study acting but within a couple of years I was working for an international theatre organisation which later developed into my years in arts television, as both a producer and director. By the time I stopped altogether in the late nineties, I was married with 3 small children. The next decade was about the children and eventually, the breakup of my marriage, which delayed my return to work. Eventually after a stint at the National Theatre as an assistant director, I was employed as a freelance producer at the Young Vic. I loved the work, but I began to question the long term sustainability of what I was doing.

I felt like I had a gash cut across my career with 10 years of child rearing and doubted that I would be able to achieve my potential in the theatre world. I wasn’t exactly treading water but I just didn’t think I would get the jobs I would have gone for had I not taken the break. Then I had this epiphany about psychotherapy – I’d always been interested in it but it had never occurred to me that I could make it my profession. I decided to train and embraced the existential path along the way. It took five years of being back at school and since qualifying three years ago, I have been successfully running a full-time practice.

FF: Tell us a little more about the first phase of your first career.

DH: I came to London with the intention of pursuing an acting career, but I realised pretty quickly that I didn’t have the capacity to live with the uncertainty that comes with being an actor. I felt my need for self-determination would always be an issue, as I wouldn’t be able to tolerate that other people would get to decide whether I was working or not. I was a very long way away from home, and basically don’t think I had the confidence to risk it. But theatre was my great passion and so I found other ways in; I began working with an international theatre organisation under the auspices of UNESCO that was all about creating cultural exchange between theatre professionals in Britain and overseas. We were part of an international movement of people who were committed to opening up what was a pretty insular British theatre culture at the time. And the work was exciting, giving me opportunities to travel and meet a lot of interesting and like-minded people.

FF: What sorts of things did you do?

DH: Having established close ties with people at various theatres who supported what we were doing, a number of opportunities started to come my way and I was able to establish myself as a freelancer working in various subsidised theatres. The founder of the Almeida Theatre, Pierre Audi, sought me out and asked me to work with him as part of his original team. I started doing press and then became the administrator of his international festivals — Pierre was a visionary and I was lucky to be part of his extraordinary achievements. My role at the Almeida later led to my being on the board for 10 years, and even serving as chairman. Meanwhile I did stints at the ICA, Riverside Studios, Black Theatre Cooperative and on the early years of LIFT (London International Festival of Theatre). They were wonderful times.

FF: How did you move into television?

DH: Having only been interested in live performance before, I became interested in television with the advent of Channel 4, which at the time was this innovative force that landed into the landscape of British television and was going to change everything. It was known that Channel 4 was going to place a lot of emphasis on its arts output, and the ethos was to challenge the mainstream which was right up my street. Through my theatre contacts, I was introduced to Tariq Ali and Darcus Howe who were setting up Bandung Productions. They employed me to use my admin skills to support this brand new production company, and in exchange I got to learn about television production. From there I moved to the ICA to help set up ICA Television, where I produced the film of Michael Nyman’s opera The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat, based on the famous Oliver Sacks case study. This film went on to have a great deal of success and it established me as a television arts producer. I produced a few more films with various directors and eventually formed my own company in partnership with a female colleague with whom I loved working. We called it Euphoria Films, an expression of our joy at working together in a female-led company..

FF: What was your favourite part of this period?

DH: I had 10 fantastic years making lots and lots of arts television — TV about architecture, TV about opera, TV about visual arts. We would take an idea to Channel 4 and if they liked it, they would give us the money to go away and make the film. By the time I left the business, they would call you and say, “we want a film about this, do you want to do it?” So instead of being artist led, it later became commission led — and that was very different. In fact, this was the main reason why I didn’t go back to TV after my career break. I no longer felt like there were the same opportunities to do the kind of work we’d been able to do in the early days because it had become a much straighter business.

Anyway, there was a golden time for me personally in terms of creativity and fulfillment in the early nineties. I had made the transition from producing to directing for my own company, which felt like a bit of a gender triumph as I didn’t want to confine myself to helping male directors realise their projects. A high point in terms of the convergence of the personal and professional was when I was pregnant with my second IVF child, and I was commissioned to make a film for Equinox, the Channel 4 science strand, about assisted reproduction. I presented the film and used my own pregnancy as a way to talk about the science of IVF as well as exploring the emotional journey that culminated in the birth of my daughter. It was a unique privilege and out of that film I became a kind of advocate for various fertility groups and even had the crazy experience of addressing the annual general meeting of the HFEA (Human Fertility and Embroyology Authority), telling all the doctors and scientists about the IVF experience from the patient’s point of view.

FF: How did you arrive at the decision to stay home with the children?

DH: So there I was with my own company and making a lot of films. Increasingly though, it felt less creative as we became preoccupied with the business side — always having to generate enough income to pay staff wages. And by this time, I had children which meant that I always literally had one foot in the office and one foot halfway out the door to get to the school concert or whatever it was. And then that important phone call that you had been waiting for all day would come in just as you had to leave — it’s a story that’s familiar to many working mothers.

The first programme that I directed was for the BBC, a documentary for Omnibus about Robert Lepage, one of my favourite theatre directors, and it meant leaving my first-born at the age of fifteen months to go and film in Quebec for a couple of weeks. And I just remember the way she held onto me when I got back – how she didn’t want to let go of me – and that was tough.

By the time I was pregnant with my third child, my colleague and I had established our offices around the corner from where I lived in order to facilitate the working mother model. Our ambition was to make a really high quality television drama — a shift from our previous documentary work. And then we received a fantastic commission to do just that but it required us to film in Belfast. Suddenly I was looking at the prospect of having to be out of London for nine months and I just thought who am I kidding? I am not going to Belfast and leaving three children behind. So basically, that’s when I faced the crossroads where I was either going to accept my children being brought up by nannies so that I could go on working, or I was going home. And I decided to go home. I’m glad I did it but it was a difficult decision at the time.

FF: And some time later, your marriage also ended. Divorce is difficult in anyone’s life. Tell us how it affected you.

DH: Just as I was getting ready to return to work, my marriage went into crisis and rushing back to the workplace was no longer my first priority. I focused instead on making my kids feel safe and helping them to manage the new reality of their changed family situation. This delayed my return to work another couple of years beyond what I had intended.

The divorce also set me back in terms of my own confidence. But you know, I don’t think that any of the psychotherapy journey would have happened if I hadn’t gotten divorced. Rupturing my status quo put my world in to this kind of free fall. Divorce had been the most impossible, alien and unanticipated thing that could happen in my world. I would wake up in the morning thinking, “No no, this can’t be my life. I just had a bad dream. That’s not me.” That was the negative side. The positive side was, “Oh I’m surviving this —anything is possible.” It showed me that you don’t just have to keep on repeating what you’ve always done. There’s this whole world out there and suddenly I was thinking, “I’m going to train to be an existential psychotherapist.”

FF: Why did you choose existential psychotherapy?

DH: I see existential therapy as the most ethical way that I can practice psychotherapy, and the most closely aligned to my political, intellectual and personal values. As the name suggests, it is inspired by existential philosophy — the philosophy of existence and the human condition — as much as it is by human psychology. It is grounded in the belief that the nature of the human condition is rooted in relatedness — being in the world with others — rather than on an idea of individual psyches and pathology.

FF: Do you see a relationship between what you did before and what you do now?

DH: I love that question! And this is where my reputation for sometimes getting carried away with my enthusiasm comes out, because I feel there is such a strong connection between my “before” and my “now”, and I love that connection. The things that drew me to acting — and that still draw me to theatre — are expressions of the same qualities in myself that draw me to psychotherapy. If there are traits that I could say are fundamentally important to me, they are around communication and connecting intimately with others. Both therapy and theatre are avenues of enquiry into the human condition, into what it is to be a person in the world. Whether it’s through art or through the dialogue of the way I practice psychotherapy, both forms of enquiry are expressions of what I find most interesting in life.

FF: What do you love most about being a psychotherapist?

DH: For me it’s an expression of my most creative self and what I value most which is connecting with other people. That I get to sit in a room with another person and have these intimate and enquiring conversations interrogating what it means to be a person in the world. And that I’ve done the work to be able to bring myself as an open and hopefully skilled person to facilitate— for another person — the possibility of connecting in a way that they find therapeutic. And I’m a different psychotherapist with every client that I see because each relationship is a unique creation. When clients come for the first time to talk about whether or not we would be a good fit to work together, I often make the point that the therapy work we do together will be utterly different from what it would be with any other therapist. It’s a completely individual subjective encounter that creates something entirely unique – like art!

FF: What’s the most important thing that you want clients to know when they come to you?

DH: I’m always honest and say I’m not going to fix you nor am I going to give you advice. We’re going to have some really meaningful conversations that will hopefully help you to become the more autonomous and authentic person that you want to be. We’re going to explore a wider spectrum of choices and probably challenge patterns. That can be difficult for those who want a ‘right answer’ – who come knowing what specific outcome they are looking for – or want to be ‘fixed’.

FF: Do you for see any limitations with how far you can go in this career?

DH: Well, one of the great things about this career, unlike many others, is that no one is going to tell me to stop because I am in my seventies or even my eighties. It would have been problematic to change careers at fifty if I thought I had to retire at sixty-five. This is one of the few professions where being old with all the experience that entails is seen as an asset instead of a problem. So I just hope to keep getting better at this.

FF: What is the impact of changing career at this stage of your life?

DH: To feel like I’m learning and growing gives me energy — and I know it’s a bit cheesy to say it but it definitely makes me feel younger. Also, to have walked away from situations where I was the boss and gone back to the beginning and started again as a novice is character building. I think in my particular field of work I am fortunate to be able to draw on all of my life experience in ways that are relevant and helpful but I imagine that anyone who has the motivation to change career at a relatively advanced age will feel similarly stimulated and energised.

FF: Any Wardrobe Wisdom?

DH: I have found that what suits me is ever evolving as I change so it behooves me to stay alert. Conventional femininity was never me and I arrived in London dressed like a tomboy/hippie. I paid close attention to women whose style I admired — real women, not the ones in magazines — and definitely benefited a great deal in my 20’s from a couple of key older women who inspired me. My best friend Vera, who was old enough to be my mother and sadly now deceased, was one of them.

What I am certain about these days — partly to do with my age and partly due to my work — is that I just want things to be simpler and simpler. I like quality but I’m not driven by fashion; I tend to invest in good things and keep them for years and years. Four mornings a week, I start at 8am having gone to bed way too late the night before. So time is very much of the essence in the morning and I want to minimise the energy I spend thinking about what I’m going to wear and have evolved a uniform which is black, navy or grey trousers and a white shirt. Never underestimate how a good a white shirt can make you feel! In the winter, I might exchange the white shirts for polo neck jumpers in black, gray and navy. Maybe occasionally, I’ll wear a nice white t-shirt with a jacket. My shoes are functional and classic like oxfords or brogues. Sometimes I will include a flash of really strong colour somewhere, in a necklace, scarf or even my shoes. And of course, my signature ear cuffs — I have had them for almost 20 years, wear them more often than not and still get a compliment on them from someone almost every day.

FF: What’s in your Prescient Pantry?

DH: Coffee and milk! Because my morning café au lait is very important to me so I have even learned to keep a pint of milk in the freezer just in case. I would really be in trouble if I woke up in the morning and I couldn’t have my latte. The food that I always have in my cupboard — artichokes in olive oil, sun dried tomatoes in olive oil, hearts of palm, berries, and green apples. And always oatmeal because all you need is water and you’ve got a bowl of porridge for breakfast, which is perfect.

FF: How do you stay strong in your mind and body?

DH: For a long time I was in my own personal therapy because that was a requirement in my training. I carried on with it because it is invaluable to have an outlet to process one’s own own stuff when I am spending days helping others with their processing. Also, I think nurturing good communications with the people who are important to you in the world is essential to your well being.

For my body, I have learned to love exercise which I only really got into at 40, once I’d had my three kids. I thought “it’s now or never” and started going to the gym — which I try to do twice a week — supplemented by running around the park if the weather is good. And I try to eat really well but by that I certainly don’t mean austerely. I have an excellent appetite and I love my food so eating for pleasure is definitely on my menu.

FF: What messages do you have for your younger self?

DH: Too many but I’ll give you two. The first is advice to myself from before I had children and it would be something about being aware of and managing the tension between the fear of failure and the fear of succeeding. I look back and I think I was very afraid of failing and succeeding at the same time. I think fear of failure is generally a fairly obvious thing to feel, but the fear of success is more subtle and complex, especially for women. It took me a while to figure that out and to address it.

And my advice to myself once I’d become a mother would be about having the courage of my own convictions and those of my children. Challenge the insecurities that lead you to listen to other people’s values and ideas. I look back on the things that I worried about in relation to my children and these were actually often anxieties that I was taking on from others. They weren’t preoccupations or values from my own deepest wisdom but at times I would allow myself to be drawn into other people’s agendas. I wasted a lot of time and energy with this and will certainly be alerting my children to it if they become parents themselves.

FF: What do you hold dear to your heart?

DH: The obvious things: my family and friends, the man that I love, my work — and also art. Art of all kinds – theatre, literature, music, visual art. Those are the things that make me feel intensely alive and make my life meaningful.

A Fabulous Fabster thank you to Debra Hauer!

Reading this was a wonderful, grounding way to start my day this morning. Thank you lovely Debra Hauer.

Fabster 2 Fabster!!!

Great interview and insight into a wonderful friend! I should spend more time in London.

Proud proud daughter. A huge inspiration to me and others I’m sure

Thanks, Hannah. Yes, your mother is indeed an inspiration to so many of us! All the best, Christine.

This is an inspiring and hopeful interview – especially for those of us who find ourselves at a life crossroads. Thank you, Debra and Christine!

Thank you, Rebecca. Debra’s interview showed me that life crossroads can be helpful in the long run if not confusing at the time. All the best, Christine

Phenomenal journey and guess who’s really come out on top of everything? What a great life!

Much love Barry

Debra, How lovely to “see” you again. You are gorgeous, and incredible in your journey. I am so full of emotion, and it is indeed trippy, to fill a gap of more than forty years from within the eloquence as you describe your immensely interesting life. With loving regards, Keri