Scary as Tea Bowls: Setsuko Sato Winchester

Artist and creator of the Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project, Setsuko Sato Winchester is a first generation American of Japanese descent. Six years ago, her husband the British writer Simon Winchester became a US citizen — a decision which propelled Setsuko, a ceramicist and former NPR journalist, to grasp the full meaning of her own US citizenship. “Being married to a writer who has written books about America, loves this country and even became a citizen in 2011, I kept running into the same questions, ” Setsuko says, “Who is an American? What does citizenship mean? and How long do you have to be here to be considered a part of this mongrel American tribe?”

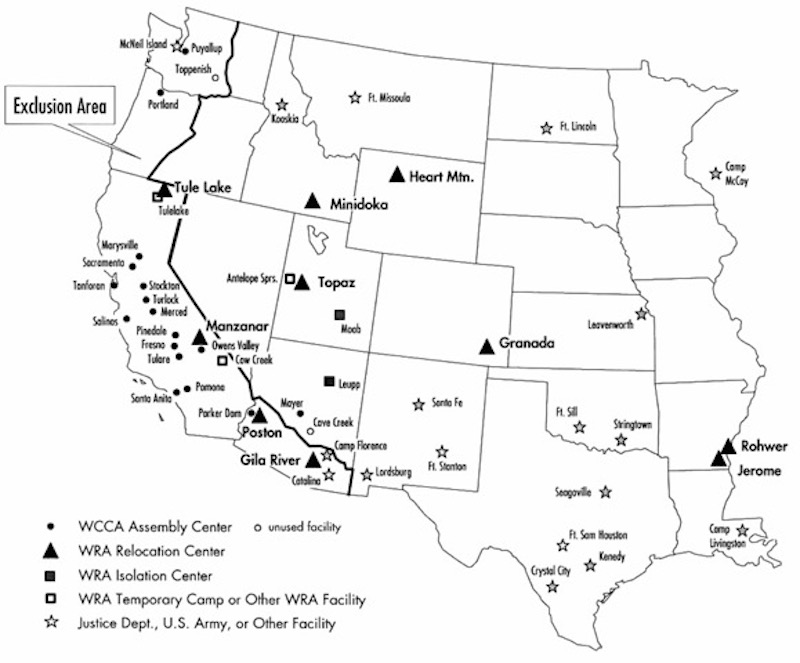

Setsuko’s initial interest in the history of Japanese Americans evolved into 120 hand-pinched tea bowls and two extraordinary road trips across America. In her Land Rover with Simon’s assistance, she drove the bowls to every one of the ten internment camps — officially referred to as War Authority Relocation (WRA) camps — where the US government had incarcerated 120,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

The result is a haunting series of site-specific photographs which contrast the yellow tea bowls against the background of each camp. Delving further into the concept of Freedom from Fear, Setsuko continues today to photograph the bowls at iconic American landmarks. Join us as we interview Setsuko to learn more about her yellow bowls and how they represent her greatest concerns for the United States at this moment in the country’s history.

Fabulous Fabsters: What is the Freedom From Fear/Yellow Bowl Project?

Setsuko Sato Winchester: My project is about the concept of “freedom from fear”: What it has meant in America in the past and what it could mean today. More specifically, it’s about how the US government — under the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration — imprisoned 120,000 people of Japanese descent, 70% of whom were US citizens, by relocating them into WRA camps in 1942.

FF: The Freedom From Fear/Yellow Bowl Project is a reaction to a relatively unknown event in US history. Can you please elaborate?

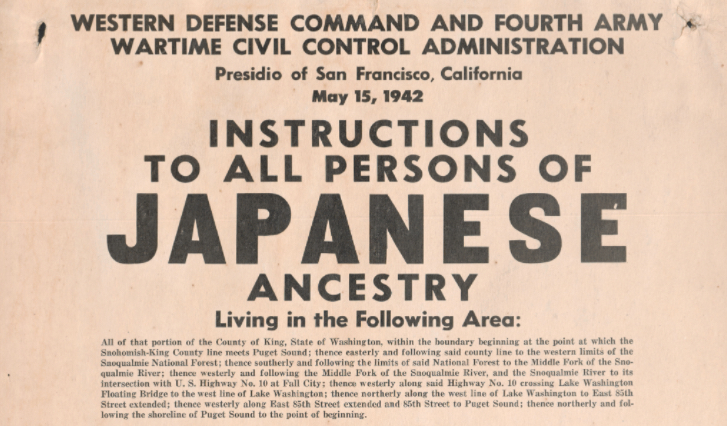

SSW: On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy led a surprise attack against Pearl Harbor, a US Naval Base in Hawaii. Immediately after the attack, the FBI rounded up 5000 Japanese foreign nationals — mostly community leaders like teachers, businessmen, heads of religious organisations- and put them into internment camps run by the Justice Department. For those remaining, the government ordered their bank accounts to be frozen, imposed a curfew and put travel restrictions on them. Two months later on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt invoked Executive Order 9066. This order gave the US military the authority to evacuate anyone whom they felt posed a military threat to the United States. While the order did not specifically state the Japanese, the US military evicted over one hundred and ten thousand people of Japanese ethnicity who were living on the West Coast — many who were US citizens — to what were euphemistically called “relocation” camps. These camps would eventually hold over one hundred and twenty thousand individuals, one third of whom were children.

FF: How did the military initiate the evacuation?

SSW: Initially, the military encouraged the Japanese Americans to voluntarily leave their homes, businesses and farms, implying that it was their patriotic duty to do so (or conversely, unpatriotic not to). The majority refused to leave without some assurances as to what would happen to their property. However, about ten thousand voluntarily uprooted their families to head East. They packed up their belongings and tried to reach family or friends in other states. But by the time they reached the borders of the next state, they found themselves rejected and not allowed to cross the border. The argument of the governors of those bordering states was that if the Japanese Americans were dangerous in California, they would be dangerous in their states as well. Those who had volunteered for eviction discovered they were stranded. Patriotic gas station owners refused to sell them gas. Store owners wouldn’t serve them and those who owned boarding houses or other establishments where they could stay turned them away — thousands were stranded on roads and sheltering in parks. The US government had essentially created a refugee situation for US citizens within their own country.

FF: What did the government do next?

SSW: As a result of this debacle, the US government ordered everyone to return and FDR proceeded to sign a series of Executive Orders that included the creation of the War Relocation Authority. This gave the military authority to forcefully remove everyone first to “Assembly Centres” — which were hastily created at race tracks or fair grounds where thousands were kept in former horse stalls — and then into 10 shoddily built concentration camps where the prisoners found new homes in overcrowded tar paper and wood slat barracks. In order to survive the cold winter weather, many of the camps were built by the incarcerated themselves because that was the quickest way of getting the structures up. Rather ironically, the prisoners built their own prisons.

FF: Where were these camps?

SSW: The camps were in some of the most desolate and forgotten parts of the country mostly out in isolated desert areas of the west. There were two in Arizona, two in California, one each in Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. Two were located as far east as Arkansas in the swamps of the Mississippi Delta flood plains.

FF: You do not have any relatives who were living in the US during the war — your own parents were not incarcerated because they didn’t move to the US until the 1950’s. How did you come to learn about this piece of American history?

SSW: In 1973, a book called “Farewell to Manzanar“, a memoir about a family’s experience in the camps was published. A few years later, when a substitute teacher in my school in New Jersey realised she had a Japanese student — me — she brought the book into our classroom. Two boys in the class said, “That would never happen here. That’s something that would happen in Nazi Germany.” Then they said that if that were true, she would know — pointing at me. I was shocked and also mortified because I didn’t know anything about it.

At the time, I tried to ask some people, adults I thought might have answers, but no one seemed to know or care much about it. Many of the Japanese Americans who had been in the camps were cast and shamed as traitors and so they never spoke about it. They were to spend most of their lives trying to prove that they were American in a country with a long history of anti-Asian legislation, originating with the Chinese Exclusion Act in the 1880’s. It wasn’t until I had left journalism and was in my 50’s that I started asking questions again and digging deeper into this story.

FF: What happened when you dug deeper?

SSW: As a former journalist, I was ashamed that I didn’t know the story of my own peoples’ history in America. And as I read, I realised that much of the fear that has been generated since 9/11 is eerily familiar — like we’re following a roadmap of the 40’s. I felt an urgent need to get this story out but I wanted to do it in a way that would be gentle and not hurtful. World War II is seen as the “Good War” in terms of heroism and pride and I did not want to belittle those feelings. But I also believed that if I as a Japanese American kept quiet about this incident, it could easily happen to somebody else.

FF: Tell us why you decided to express this story through your ceramics.

SSW: In 2014 we were out in LA at an event related to one of my husband’s books. At a fancy dinner afterwards, I found myself seated next to the chair of the event. We started talking about California history and then about my research into the history of the “internment” camps in the 40’s. I said that growing up on the East Coast, we weren’t taught about this part of US history. I wanted to know what they were teaching the children on the West Coast where the incarcerations occurred. She said, “My dear, that was a very unfortunate sequence of events. But it was something the government had to do. The government did it to protect the Japanese people.” “That’s very interesting,” I said out loud while thinking to myself, “Wow, that’s alarming — is that what they’re teaching the kids here?”

I came home and just started pinching bowl after bowl — it was like a physical compulsion. The bowls in my mind were people. They were families — moms, dads, children, grand-parents. Each one was an individual — farmer, doctor, artist, carpenter, journalist, dentist, carpenter, gardener, painter, sculptor, musician, banker, Buddhist, Christian, and so on. I also varied their sizes — from very small to the oversized — representing the fact that those incarcerated ranged across the human spectrum, as tiny as babies, as large as Sumo wrestlers. I made one hundred and twenty bowls, one for every one thousand people who were incarcerated in these camps.

FF: And the colour yellow?

SSW: I chose yellow to represent The Yellow Peril as the Japanese American population was referred to at the time. The different shades and combinations of yellow glazes helped me group the bowls into families. I wanted to show that the incarcerated Japanese American families were as threatening as a bunch of tea bowls.

FF: Why bowls? And why did you hand pinch them?

SSW: For the Japanese, ceramic pots are the architecture of life. There is a pot for every occasion from the ordinary to the celebratory to the solemn. I chose the tea bowl because the philosophy of Japanese tea is to celebrate humanity. A tea bowl fits in the palm of your hand — human scale.

I hand pinched them because I like the irregularity of the handmade where no two are the same. The simple act of sharing a cup of tea is about taking the time to stop and acknowledge the other person, extolling simplicity over complexity and celebrating beauty in the everyday. We’re all imperfect but in the end, life is a gift. Like cherry blossoms — no two petals are exactly the same but together they are beautiful.

A handmade tea bowl may not be perfect, but it has soul. This seemed a natural way for me to bring art, history and my personal journey together.

FF: Why did you want to go and visit the camps?

SSW: I wanted to see for myself what these places were like and what actually remains from that time. My original plan was to go to every camp and leave one hundred and twenty bowls to memorialise what happened there and to acknowledge and thank those fellow Americans who came to this country before me.

FF: An ambitious plan. What happened?

SSW: The logistics, time and distance in terms of travel and the physical act of taking and leaving two large boxes full of one hundred and tea bowls at each of these remote areas proved daunting. I had also developed carpal tunnel syndrome in my right hand and had to limit the number of bowls I could pinch to ten a week. Then in 2015, an opportunity arose where we had to be in southern California by a specific date 3 months ahead in December and we decided we would drive there from Massachusetts on the East Coast where we are based. The three months was just enough time to make the last few bowls and plan our trip.

FF: How did you use the cross country drive to further the intentions of your project?

SSW: Another part of my goal was to bring this story — one that has mostly remained on the West Coast — back with me to East Coat. As a photographer, I’ve always been intrigued by the phenomenon of the Travelling Gnome. A prankster takes his neighbour’s garden gnome and photographs it at famous landmarks around the world — like in front of the Eiffel Tower — and then sends the image back to his neighbour to let him know what a fabulous time his garden gnome is having. It’s a playful and intriguing form of documentation, which eventually became a global online phenomenon with many creative versions. I decided to take that contemporary meme and twist it a bit by taking something that wasn’t easy to carry — one hundred and twenty delicate little bowls packed into two huge boxes —to places where no one wants to go, the camps. I documented the journey of the bowls with photographs and put them on my website — Freedom From Fear/Yellow Bowl Project. My hope was that if I could get people to look at the tea bowls and become curious about them, they might want to know where they went and why.

FF: What keeps you up at night?

SSW: In December 2015, Donald Trump — before he won the presidential election — invoked FDR many times as a good man and a good leader. At the same time, he also cited FDR’s “internment” of the Japanese during World War II as a possible line of action for the US to consider with regard to our current immigration problems. The following spring, I visited Tule Lake, one of the camps in northern California. The National Park Service officer there told me that ever since Mr. Trump had invoked FDR and “internment”, the camp had seen an increase in visitors who had never heard of the camps before. Their reason for coming? They were curious about how the camps might work now. If history is prologue, then other Executive Orders are sure to follow along with the selective enforcement of increasingly restrictive legislation. The Freedom From Fear/Yellow Bowl Project is not about Japanese people nor is it about Asian history. It’s an American story about what happened to Americans in America and asks, “Who is an American?” and more importantly, “Could it happen again?”

A Fabulous Fabster thank you to Setsuko Sato Winchester.

What fantastic work. A great example of how artists’ work can convey powerful messages in such innovative and meaningful spaces.

And such a relevant message for today! All the best, Christine

I am so intrigued to learn about your work. The process of creating your pinched pots, their form and colour as well as the site specific displays really speaks to me as a maker, knowing how you completed a circle in your creative process. But even more, the subject of your work and relating it to events today and as well as 1942 also resonate. My mother had just graduated teacher training in 1942 and was shocked at the injustice to ‘Japanese Americans’ in the 1942 Executive Order. She became a teacher at Manzanar living in the barracks and teaching the younger children through 1944. The experience prompted her to become a social worker, working with refugees after the war, where she met my father, a Polish refugee who had been imprisoned in a Japanese POW camp from 1942- 1945. Your poetic voicing of Freedom of Fear, at a time when we once again fear for our freedom of speech and movement is a poignant reminder of the fragility of these freedoms and the lessons of history we must remember .

The author writes about Japanese internment as “a relatively unknown event” and I feel this is an indictment of either this website’s audience or the author’s generation. I am heartened the artist brought attention to an historical matter that has much relevance today.

Oh, let me retract my own comment. I realize now this is a British based publication (I stumbled upon through a Remodelista link) and we all can’t be expected to know each other’s historical domestic blunders. And I’m guessing that many of us here in America are in a bad mood lately, watching the resurgence of old debacles.

Hi Dani

Thank you for your interest in this post and your retraction! I was born and raised in America and have lived in the UK for 22 years. Like the artist, I grew up on the East Coast, did not learn about Japanese internment in the classroom and therefore did not know any of the details. I phrased the question the way I did so that we could make sure that audiences anywhere around the world would receive the basic facts in order to fully understand the events which, I agree, have so much relevance today. And I truly empathise with the bad mood.

All the best, Christine.

Even before your gracious reply I belatedly realized why you posed the topic in an accessible way for your thoughtful in-depth article. Mea culpa, again. My mom walked past internement fences everyday to grade school in Stockton and never forgot the horror of it. She took care to teach us the stories. My uncle built homes in Sacramento and was the first to make them available to Japanese after the war….

Hi Dani

Thank you again for writing in. I was very moved to read about your mother’s experience of walking past the internment fences on her way to school and about the homes your uncle built. Wondering if you read the comment ahead of yours by Deborah Werbner about her mother’s experience? Let’s just hope we can keep from making similar mistakes again.

All the best, Christine.

Impressive and thought provoking work Christine. Thank you for the art, for the reminder, and for the warning.

And thank you Scott for taking the time to read and comment. I’m glad you were able to take something meaningful from this story. All the best, Christine.

What a great project, it is so important that we don’t forget our past, whoever and wherever we are in the world. I remember visiting Dachau and reading the inscription on the memorial “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

To convey this message with such beauty – Christine is so talented. I am in awe.

Dear Karen

Many thanks for your kind words about the post. I am thrilled that Setsuko’s story spoke to you.

All the best, Christine.

Thank you for your thoughtful, quietly provocative efforts on behalf of those Americans who may not be recognized as such by some, in this very perilous and indeed scary time in our country. All of us need to remember that we all have different shades of color, all of us belong to different groups in some way or another, but we are all Americans.

Thank you for writing in Annilee. In a recent trip back to the States, I picked up a copy of “It Occurs To Me That I am America”, a collection of essays and artwork by American artists that speak to the what it means to be American. If we can hang on to these stories, we can hopefully create a new narrative out of what is happening now. I highly recommend it. Best. Christine

Hasn’t anyone read “Snow Falling On Cedars”, a novel, written in the nineties, by David Guterson? A beautifully told story of the distrust and paranoia in a small West coast island community before, during and after WWII. The imagery conjured by Setsuko Sato Winchester in her installations is reminiscent of the feeling in the book: Spare, elegant and poignant.

We too in Australia had internment camps, but I don’t remember their history being part of the school curriculum.

Thank you Susan for reminding me of “Snow Falling on Cedars”. It’s a book that I have always wanted to read and will make a point of doing so now on your recommendation. Best. Christine.